Shared from the Boise Weekly story on July 29, 2020 by Sydney Kidd

The Voices of History’s Unheard: Here’s what’s behind the recent removal of many Indigenous-themed Idaho high school mascots

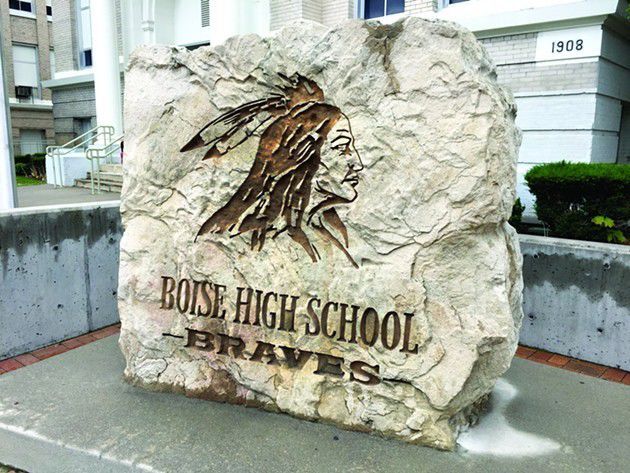

Boise High School Principal Robb Thompson had been considering changing the school’s mascot, “the Braves,” for quite some time. However, when he broached the topic with some members of the community, the same response kept coming back.

“There is this mythical letter of support that Boise High had from, I think, the Coeur d’Alene tribe, saying that it was OK for us to be the ‘Boise Braves.’ And I’ve searched high and low, and couldn’t find any such letter,” Thompson said. “And I thought, ‘Well I’m just going to reach out to local tribes and ask them because I’ve only seemed to have heard from non-native people about this.’”

Thompson reached out to the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes, who once lived in the Treasure Valley before being resettled by the federal government to the Fort Hall Indian Reservation. Once he found the tribes did not approve of the mascot, he asked if they would send a letter to Boise High to publicly voice their stance on the issue. Last summer, the tribes did send a letter and also sent one to the State Board of Education requesting the removal of seven other schools’ mascots.

For years, the debate over whether or not to change Indigenous-themed high school mascots has seemed to revolve around non-native people reacting to the requests of their local tribes. Many have contested these requests, calling it an erasure of longstanding traditions. Others maintain that the tribes have always approved and even been proud of their school’s Native American mascot.

In recent years, the Nez Perce and Shoshone-Bannock tribes have advocated for the changing of Indigenous-themed mascots in Idaho’s public high schools. Within the State of Idaho, there are still eight high schools with Native American mascots. This number used to be 11, but in the past 13 months, Boise, Teton and Nezperce high schools retired theirs. In each instance, it took two-way communication to finally send the monikers of “Braves,” “Redskins” and “Indians” packing.

Many have wondered why Native American tribes haven’t said anything until recently if they found the mascots so offensive. According to Shoshone-Bannock Public Affairs Manager Randy’L Teton, tribal leaders in the past focused on other initiatives and didn’t feel like they had a place at the table to say anything about the mascots.

“We didn’t have any part or say when these things were created or these logos or mascots were created,” Teton said. “The tribes were never officially contacted to have any comment or insight of making sure it was culturally appropriate. So that’s what we’re doing now, is just saying going forward for our future youth, let’s start talking about making things right.”

“Making things right” was exactly what Thompson tried to do when working with the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes in retiring Boise High’s mascot. He said that the working relationship between the school and the tribe was one of the greatest things to come out of the process.

“I think the first step for any group that’s looking at that question is to reach out to their local tribe,” Thompson said. “One of the most enlightening and helpful things for me was to hear it from the perspective of them—because I can’t walk in their shoes, I’ve never walked in their shoes. So I, as a school leader, felt like it was really incumbent upon me to do everything I could to educate myself and to understand their perspective. … Native Americans are not a part of our past. They aren’t history. They are a living, breathing group of people among us. And anything that we do—whether it’s intentionally or unintentionally—that makes them feel not as welcome as any other person is inappropriate, quite honestly.”

According to letters sent by the Shoshone-Bannock tribe, Indigenous-themed monikers like “Braves” and “Redskins” do not honor Native Americans because they perpetuate the ideologies of white settlers during the colonization of what’s now the United States, when Indigenous people were persecuted. The letters said that the mascots ignore why Native Americans had to be “brave” and that a “redskin”—though one Native American organization, the Native American Guardians Association, says the term has historical significance—is a reference to the bloody scalps of Indigenous people that were collected for proof of bounty on dead Native Americans. The letter said other such mascots also present a problem of cultural misrepresentation or misappropriation, and contribute to the bullying experienced by Native American youth.

Changing the mascot, Thompson said, went relatively smoothly, with minor backlash. Teton said the mutual, working relationship she experienced between Boise High and the tribe was the kind of relationship she seeks to have with each of the schools she works with. However, even with the best intentions of school administrators, this has not always been the case. Take the case of Driggs in the Teton School District.

TSD Superintendent Monte Woolstenhulme said he first broached the subject of changing Teton High’s Redskins mascot about 6 ½ years ago, when he received letters from the Shoshone-Bannock and Nez Perce tribes; but he received significant community pushback at the time. In the wake of dealing with budget cuts, the school board killed the discussion. It wasn’t brought back up until March of 2019, when a community member raised the issue again in a school board meeting.

Teton School District hosted public education forums and invited members of the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes to give a presentation on their history and why they wanted the mascot changed. According to Teton, despite the attempt at two-way communication, the presentation was not well received by many in the Driggs community.

“Here we are, the original tribe, speaking about our history that is inclusive of that area, and they didn’t want to hear it,” Teton said. “So it was really hard, you know, to try to educate in a very professional, respectful manner because they were yelling at us and they were just very adamant. They just didn’t want the change. … It was weird. I’ve never experienced that type of vibe, the energy in that room when we were talking about this.”

Despite the ill feelings about retiring Teton High’s “Redskins” mascot, Woolstenhulme, students and community members who stood by the tribe and championed the cause eventually saw their efforts bear fruit. This June, students selected the “Timberwolves” to become Teton High’s new school mascot. Even so, hard feelings remain in Driggs.

“I think it will take time for the community to move forward with this,” Woolstenhulme said. “Some are excited for the change and still some are very upset that the change is happening.”

Up in northern Idaho, a more pacific process recently took place revolving around a friendship. Before Shawn Tiegs was the Superintendent of Nezperce School District and Bill Picard was on the Nez Perce Tribal Executive Committee, they were two friends who coached against each other in basketball.

According to Picard, one day, after they had both been selected for their respective positions, the topic of the “Indians” mascot came up.

“We just started visiting,” Picard said. “I told him it was kind of awkward for the Nezperce cheerleaders to cheer ‘Let’s go Nezperce Indians!’ when they’re sitting in the crowd with Nez Perce Indians. And he said, ‘I never thought of that before.’”

The Nez Perce tribe had actually sent a letter to the school board in 2014 asking the board to consider a mascot change, but this was before Tiegs was hired as superintendent. According to Tiegs, the letter was discussed and the request went largely ignored. At one point, Picard told Tiegs the tribe was planning on sending another letter, but Tiegs asked him to hold off, fearing the situation would turn into an “us-vs.-them” scenario.

“I said, ‘You know, Nezperce is an incredible town with very thoughtful people. And yes, we’re kind of a conservative town and yes, we like our history, etc. But give us a chance to have a conversation without making it a fistfight or a big disagreement,’” Tiegs said. “This isn’t about ‘us-vs.-them,’ or ‘we and them.’ It’s just about making a good decision and kind of moving forward with it.”

On July 13, after many discussions, the Nezperce School Board voted to remove the mascot.

Picard retired from NPTEC in June, but he was still the first one Tiegs called to tell about the mascot retirement being official. Picard said he couldn’t have been happier to hear the news.

“I was elated. I actually told my wife, I said, ‘Man I just feel like jumping up and down and screaming,’” Picard said. “People have been making fun of my family for years, and I felt like now somebody stepped back and said this is wrong, and it’s time to correct it. And so I just really felt excited.”

According to Picard, the tribe has offered to buy the school new athletic uniforms once they decide on a new mascot. Picard said he is happy with how each side worked together for a mutually beneficial outcome. He hopes this process will act as a springboard to further a close relationship between the tribe and the people of Nezperce.

However, not every scenario plays out with communication and change. More often than not, the tribes’ requests have been met with radio silence. In fact, Teton said no other schools besides Boise and Teton High have reached out to the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes since they sent the 2019 letter.

The lack of response to the letter shows disparity with many schools’ previous claims of having open dialogue with the tribes. In 2019, representatives from Pocatello High School told the Idaho State Journal that the “Indians” mascot represents Native Americans respectfully and that the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes have been “proud” of the mascot.

But Teton said this isn’t necessarily the case, citing an incident that occurred at a Pocatello High pep rally this spring, in which a routine performed by the dance team caused Shoshone-Bannock youth to feel mocked.

“The pep rallies made them feel like they were being made fun of, and they felt embarrassed and ashamed, and why would you do that?” Teton said.

Boise Weekly reached out to the Pocatello/Chubbuck School District several times for comment, but a spokesperson said the school district had no comment and current conversations about the mascot are informal.

In the cases of both Boise and Teton High, one thing has been made clear to Thompson and Woolstenhulme: There is a need for more Native American history to be taught in current school curricula.

In Nezperce, such a curriculum already exists. In a town of just over 450 people, a Pacific Northwest History class is required for graduation from the local high school. The class has been taught since before Tiegs graduated from Nezperce High in 1998, and covers the history of the Indigenous people who first lived in the area. The district has received multiple education grants from the Nez Perce Tribe for the class. According to Melanie Cronce, who teaches the semester-long class, the curriculum focuses on topics like Indigenous migratory patterns, the differences between coastal and plains tribes, their experiences with explorers and Christian missionaries, and the Indian Wars, with a special emphasis on the Nez Perce War. The school even includes resources from the Nez Perce Tribe like videos of tribe members telling their stories.

“My Pacific Northwest History class is the story of the people of our area, all who have a story to tell,” Cronce said. “I emphasize that we all need to examine history from the viewpoint of all those involved and most particularly the voices who are usually less heard. They are the ones with the real story to tell about history.”

According to Teton, education is an important step in the process of creating more social and cultural awareness of Indigenous people. She said education, as well as cultural sensitivity training for teachers, are needed to help create an environment of inclusion and respect for Native American youth in Idaho schools.

The Boise School District, according to Thompson, is currently trying to weave more extensive study about Idaho Native American culture into existing curriculum.

“I think for us as school officials it’s so important to approach things from a perspective of when we know better, we do better. And also to be continuously evaluating our system to make sure that everybody has opportunity is welcome, feels nurtured and is cared for in an equal manner,” Thompson said. “It’s okay that our school changes and evolves to meet the needs of our students. And one of the needs that our students have right now is definitely an understanding of how all of this stuff works in the world around us, and how we all need to put our best foot forward.”