Media share from The Seattle Times in regards to other tribal members along the river and how the dams have changed life for many.

Original article found here:

ARTICAL SHARE:

By Lynda V. Mapes Seattle Times environment reporter

LONE PINE IN-LIEU SITE, Wasco County, Oregon.

Indian fishing platforms cling precariously to the rocks, part of a way of life on the Columbia River persisting for more than 10,000 years.

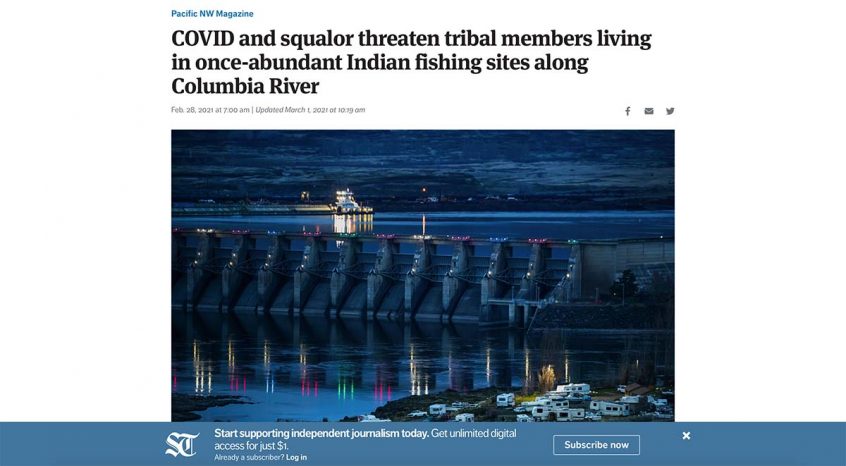

The Dalles Dam looms just upstream, a concrete behemoth generating power that surges throughout the West. Yet, Indians living just across from this dam flocked on a recent winter day to a visitor from the Portland-based WAVE Foundation who was passing out donated generators. Fired with fossil fuel, the generators offered a coveted chance for a bit of electricity for Indians living in ramshackle trailers and makeshift shacks in this, one of the world centers of hydropower.

It didn’t have to be this way; back when Bonneville Dam (located about 50 miles downriver from The Dalles Dam) first was built, beginning in the 1930s, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers carefully relocated the mostly white settlement of North Bonneville at a cost of $35 million. Yet, a 2013 review by the Corps’ Portland District found as many as 85 Indian families that lived on the banks of the Columbia before the Bonneville and The Dalles dams drowned their homes never received the replacement houses the Corps promised.

It wasn’t until 2011 that the Corps finished work even on replacement fishing sites lost to the floodwaters, such as the site at Lone Pine. The 31 sites up and down both sides of the river were designed primarily for day-use fishing and some temporary camping. But out of a need for housing and a desire to be closer to the Columbia, where their cultural heritage lies, many tribal members now use the sites as permanent residences. The encampments are overcrowded, unsafe and unsanitary, with entire communities relying on a single water source, and people living in makeshift shacks and broken-down trailers replete with fire, structural and health risks.

1 of 2 | Trailer houses and belongings sit at the Lone Pine In-Lieu Fishing Site near The Dalles Dam in the Columbia River Gorge. The coronavirus pandemic has brought increased pressure to the health and… (Andy Bao) More

At Lone Pine, blankets and boards cover broken windows on trailers and campers, some of which don’t even have doors. There is only one bathroom and two outdoor water spigots. One picnic shelter has been walled off and is being lived in, but two other picnic shelters have burned down. There is no fire hydrant at this encampment, and only one rutted lane, in and out.

The death from COVID last year of a beloved elder at one of the camps shows how real the risk is to nearly 200 people who live in these camps year-round, including children — a number that soars to more than 400 during the height of the salmon fishing seasons.

So far, thanks in part to efforts by volunteers and local health departments, and services provided by the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission, which has redeployed itself to help fight the pandemic in the camps, COVID cases have remained low. But the risk is anything but.

“It keeps me up at night,” says Bryan Mercier, a Grand Ronde tribal member and Northwest regional director for the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the federal agency charged with serving area tribes.

Meanwhile, federal money for maintenance and operation of the camps, including law enforcement, that was supposed to last 50 years is nearly gone in 20 — and runs out next year, even as COVID increases costs for cleaning and sanitation.

“It’s a major concern — some of these sites have running water; some of them don’t — when you are supposed to be keeping yourself healthy and clean,” says Kat Brigham, chairman of the Board of Trustees for the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation. The Umatillas are one of four tribes with treaty-reserved fishing rights on the river that authorize them to use the fishing sites. The others are the Yakama Nation, the Nez Perce Tribe and Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs Reservation in Oregon.

It especially stings, Brigham says, that North Bonneville today is a community with so many homes, some with three-car garages. It’s next door to the Third World conditions at the fishing sites, yet seems like a different country, with broad paved streets, sidewalks and streetlights, ball fields, a school, even a golf course.

“Those people got new homes in nothing flat,” Brigham says of North Bonneville. “We are still waiting. And we still have [fishing] access sites that need to be upgraded just to be healthy.”

LANA JACK RAISES a drum and her voice to these waters still as a lake, a glassy calm reservoir backed up by The Dalles Dam, completed in 1957.

As she walked the shores of Lake Celilo, Jack, a Celilo Wyam Indian, raised a grief cry and a song to the eagles that still come here, fishing for salmon. Just like the Natives who never have left this river, even as the salmon runs diminished to a tenth of their original abundance, even in a good year.

Some of the River Indians, as they call themselves, never enrolled in federally recognized tribes, nor did they relocate to reservations created far from the river. Their way of life along the river is far older than these camps, or these dams.

Jack, who lives at Celilo Village, upriver from The Dalles Dam, has for six years tried to help out as a volunteer in the camps, bringing donations of food, warm clothes and COVID prevention supplies. On a recent day, she visited the Lone Pine and Lyle fishing sites, handing out food, coats and gloves. At Lyle, Yakama tribal member Martha Cloud, 59, gladly accepted a new jacket, but she wanted and needed no pity. She loves living along the river. “It’s where we’ve always been.”

Even people who left the river have never forgotten it. Tony Washines, 75, a Yakama tribal elder, remembers hearing the roar of Celilo Falls as a boy, and watching his relatives fish. He grew up at Rock Creek on the Washington side of the river. It was a hard life in ways: Washines over the decades lost both his father and a nephew to fishing accidents on the Columbia.

But it was a beautiful life, too, Washines says, in a tight-knit community sustained by the waters and the lands of the Columbia. There were blackberries and protein-rich acorns his grandmother picked by standing on the saddle of her horse. Hazelnuts, grouse, ducks and geese. There were deer, and wild carrots, and bitterroot. And of course, always, the salmon. “We were rich.”